Lott and Thurmond

A Lott of Storm over Strom

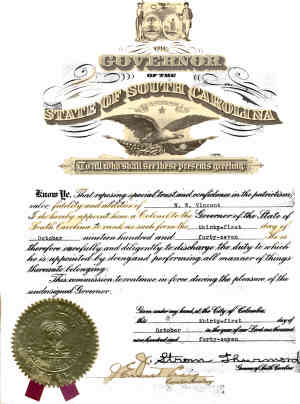

My Daddy’s brother, my Uncle Charlie, graduated from Clemson with J. Strom Thurmond in 1923, and Thurmond made my Daddy an honorary colonel on his staff in 1947.

I keep this aging document on the wall of my study.

Thurmond is the consummate politician — he knew long before Tip O’Neill that all politics is local — he serviced his district, and he knew his folks well. Let a person’s child get an award, and it be written up in the newspaper, and that parent would get a personal letter from Strom — I’ve got at least one filed away that he wrote to my folks about me. That’s why the old gentleman is still in office after all these years.

In 1948, Thurmond

and a large number of Southern Democrats rejected their party’s nominee,

President Harry S Truman. The

reason was Truman’s 1948 civil rights package which included four

primary pieces of legislation: abolition of the poll tax, a Federal

anti-lynching law, desegregation legislation and a permanent Federal

Employment Practices Committee to prevent racial discrimination in jobs

funded by Federal dollars.

The fundamental

issue in 1948 was the Tenth Amendment to the United States’

Constitution: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the

Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the

States respectively, or to the people.”

In other words,

it wasn’t that Strom Thurmond and the rest of the Southern Democrats

were against laws banning lynching; it was that they believed that these

were rightly covered by the laws of the individual states and were not

Constitutionally a legitimate part of Federal law.

That’s why the “Dixiecrats” were officially called the States’

Rights Party.

Behind these

legal skirmishes was the issue of who would enforce the law.

In many places in the South of my birth, local sheriffs would

simply look the other way on matters pertaining to the violation of the

civil rights of African-Americans. That

is why Harry Truman, having integrated the United States military, pushed

to make these things violations of Federal law — he knew that the local

authorities in many places were either unable or unwilling to protect

African-Americans from the systematic violation of their Constitutionally

guaranteed rights.

This legal battle

goes back to the aftermath of the War Between the States, when the

logically consistent, eighteenth century Constitution was changed into a

document with a measure of tension within it.

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments sowed the seeds

of destruction to the principles enunciated in the Tenth Amendment.

A movement that began with Abraham Lincoln and climaxed during

Reconstruction, receded in the decades that followed, and Jim Crow laws

were quickly passed in order to restore the civil order of White rule.

But the push for centralized, Federal control was revived during

the Great Depression by Franklin Roosevelt and then aggressively applied

to protect minority rights under Truman.

This is what Strom Thurmond saw, and this is what he opposed in

1948. But Truman won over

Dewey and Thurmond, and the Federalizing juggernaut took off.

Then came the

Eisenhower years: the Brown

family sued the Topeka, Kansas School Board; the Brown’s attorney,

Thurgood Marshall, argued and won their case before the United States

Supreme Court in 1954; Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a

Montgomery, Alabama bus to a White person in 1955; and Eisenhower sent

troops into Little Rock, Arkansas to force the desegregation of Central

High School in 1957.

After Eisenhower,

came the charismatic, but somewhat politically inept, rich man’s son,

John Kennedy, whose death paved the way for the non-charismatic, but

extremely politically skilled, Lyndon Johnson, who passed a wide range of

Federal laws that overturned all the Jim Crow Laws, but one, in the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. The last Jim Crow Law was overturned in the Voting Rights

Act of 1965. Then came

Johnson’s “Great Society” legislative package, so full of weal and

woe.

These were

turbulent years: the

political assassinations of two Kennedys and a King, the increasingly

violent struggle over the War in Vietnam, the sexual revolution, the

radical Federalization and secularization of the public school system.

Trent Lott was speaking from his heart, as a son of the South, when

he said of the hundred year old Strom:

“You know, if we had elected this man thirty years ago, we wouldn’t

be in the mess we’re in today.”

In a certain

sense, this conflict is an issue of people believing that the ends justify

the means. In the minds of

those who stood with Harry Truman, the egregious, systematic abuse of

African-Americans in many quarters of the old South, justified using one

part of the United States’ Constitution to distort the original intent

of another part of that document. From

the perspective of many in the South, they were taking a principled stand

based on loyalty to the Constitution of the United States, just as their

ancestors had done in 1860 and 61, when eleven Southern states

Constitutionally seceded from the Union. From the perspective of many of those outside the South and

most African-Americans in the South, this was but a hypocritical ruse to

maintain White dominance over African-Americans.

That is why when

Thurmond bolted the Democratic Party in order to bolster the campaign of

1964 Republican candidate, Barry Goldwater, many Southerners concluded

that the Republican Party had become the new bastion of states’ rights.

The most brilliant political leader of the last half of the

twentieth century, Richard Milhous Nixon, saw the opportunity and formed

his Southern Strategy, and a trickle became a torrent — I was at Martin

Luther King’s funeral in 1968 and witnessed the crowd chant as Nixon

approached the church, “Here comes Tricky Dick.”

That is why so many African-Americans in the South believe that the Republican Party is simply a new generation of Dixiecrats, the party of Thurmond, with his opposition to a Federal anti-lynching law. That’s why Lott’s faux pas, an encore from several other performances over the years, is so very serious — he confirmed the worst suspicions of Black America. It is also why not a few African-Americans in the South don’t believe that a real Christian can be a Republican. Me? I pray regularly with at least two Republicans whom I know are Christians: my dear wife and an African-American, Baptist pastor.

For a biblical

perspective on politics from the pulpit, you might enjoy reading this.